The Science of Javelin

What goes into a long, medal-winning javelin throw?

Javelin throwing is a highly technical event and requires perfect coordination of multiple joints in different planes of motion.

The distance a javelin is thrown is affected by factors such as wind speed and direction and the aerodynamics of the javelin. But the two most important and controllable factors are javelin release speed and release angle.

Three steps to a speedy release

1. Run up and crossover steps: a javelin throw involves a run-up of six to 10 steps, followed by two or three crossover steps before the thrower releases the javelin.

The first running steps are used to build the speed and rhythm of the thrower. The thrower then moves into crossover steps facing the side. These allow the thrower to continue to increase speed while setting up for an good release position.

The average maximum run up speed of an elite thrower ranges from 5-6m/s (20km/h), but elite throwers release the javelin at 28-30m/s (100km/h) so most of the final release speed is created in the “whole body” action of the final two steps.

The second-last crossover step, known as the impulse step, is slightly exaggerated to allow the thrower to land with their weight over their back foot, a similar movement to a cricket fast bowler. It makes sure the thrower is in the right position to start the throwing motion.

2. Transfer: the final step, known as the delivery step, allows the thrower to transfer the momentum built from the run up into the javelin. This is achieved in a movement that moves from the centre of the throwers body to the end of the throwers limbs. It is a whip-like transfer of energy from the hip to shoulder to elbow to javelin.

The delivery begins as the thrower lands on their back foot with a long straight arm and the javelin tip in line with their eyes.

The first movement is to begin rotating the right knee and right hip while maintaining the position of the upper body.

The front foot is planted with a braced straight leg with the aim of “blocking” and minimising the bend of the knee, so that the thrower’s right side quickly moves around the left.

A force six to eight times the athlete’s body weight is created at front foot contact. A bent or “soft” knee will result in a loss of energy transfer, so it’s important for javelin throwers to develop the leg and ankle strength to handle these large forces.

3. Delivery and recovery: once the front foot is down, the motion of the upper body begins. As one joint – such as the hip – reaches the end of its range of motion and decelerates, the next joint – the shoulder, then elbow and finally the javelin – is rapidly accelerated.

The final result is a high release speed on the javelin itself.

The javelin is thrown over the top of the shoulder with a bend in the thrower’s side, similar to a fast bowler. But javelin throwers, unlike fast bowlers, are required to come to a complete stop before the foul line within one or two steps of release, creating a huge amount of stress on lower body joints.

Angle of release

The second important parameter is the angle at which the javelin is thrown. The best angle of release for a javelin is between 32º and 36º, but this is tough to achieve consistently.

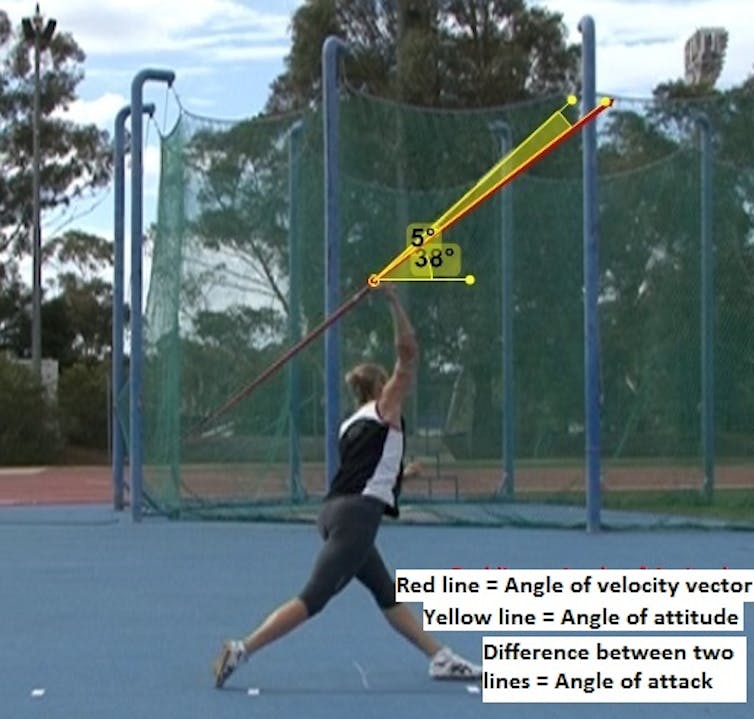

The flight path and distance of the javelin depends on the angle of attack, which is the difference between the:

- angle of attitude: the orientation of the javelin to the ground

- angle of velocity vector: the flight path of the javelin’s centre of mass (not the tip).

The ideal angle of attack is zero degrees.

If the angle of attitude is larger than the angle of velocity vector, the javelin won’t travel in the most aerodynamic way. Its increased surface area will slow it down and decrease the throw length, especially in a headwind.

A common cue from coaches is to “throw through the tip” to help throwers control the release angle of the javelin.

Often, the best thrower is the one who is able to control the angle of release with the prevailing wind. The Aussie women have done the nation proud – let’s hope their male counterparts are up to the challenge! ![]()

Mike Barber, PhD scholar in Biomechanics at Victoria University and, Australian Institute of Sport

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.